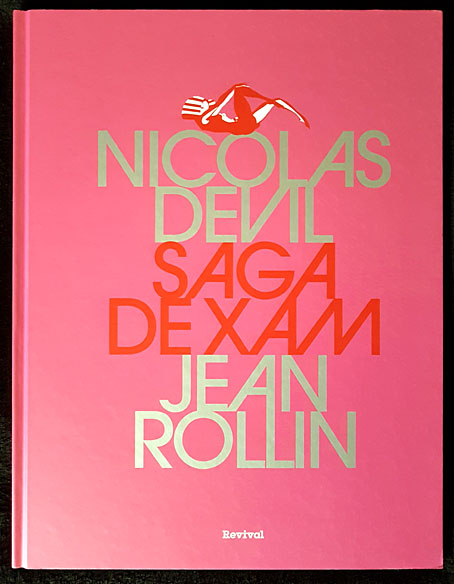

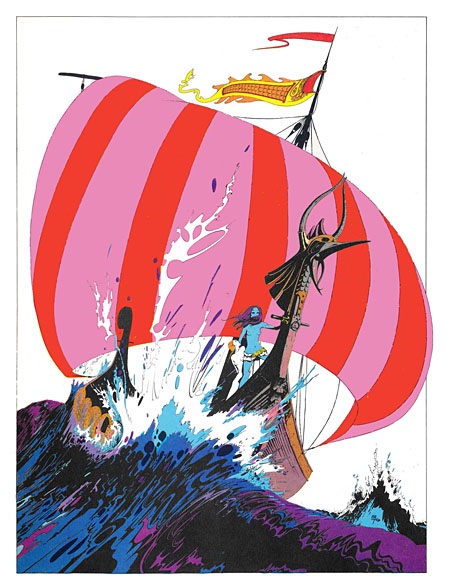

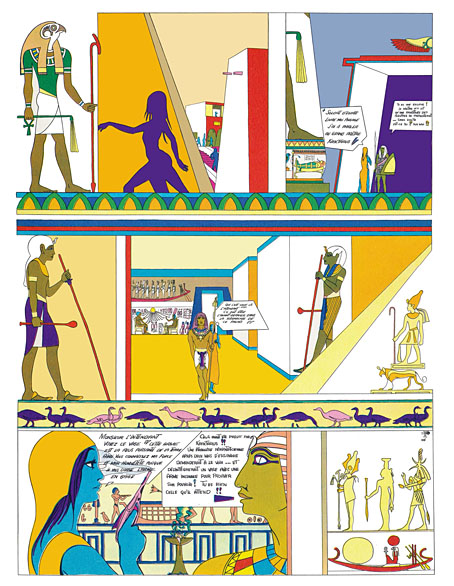

Saga est magnifique. Saga a la peau bleue. Saga est une extraterrestre. Envoyée par la reine de la planète Xam, la voici qui parcourt la Terre à plusieurs époques, traitées dans des styles différents. Son but: découvrir la quintessence artistique, politique et poétique de notre belle Terre. Marquée par l’Art nouveau, le psychédélisme américain, l’érotisme des années 1960 et la contreculture occidentale, Saga est une oeuvre hors norme et inclassable, dessinée sur des formats géants et publiée une première fois par Éric Losfeld en 1967. Hélas, le livre est très vite épuisé et devient un objet pour les collectionneurs. Cette édition reprend l’intégralité des planches de Saga, renumérisées et dotées d’une nouvelle mise en couleurs fidèle à l’originale. Saga peut enfin repartir dans une nouvelle… saga.

Here’s a book I never expected to see in a new edition. Saga de Xam is a 100-page bande dessinée depicting the time- and space-voyaging adventures of a blue-skinned alien woman, Saga, newly arrived on Earth from the planet Xam. The Xamians are a race of humanoid lesbians (their reproduction is parthenogenetic) whose planet is at war with the masculine Troggs; Saga has been sent to Earth to find a way to combat the Trogg invasion, an expedition that instructs her in the propensity of humans towards conflict and violence. The story was drawn by Nicolas Devil, with contributions from guest artists, and based on an outline by Jean Rollin which had been intended originally for a science-fiction film. There’s no need to go into detail about this cult item, I wrote about it at length several years ago after a couple of its pages stimulated my curiosity when they turned up in an exhibition catalogue. The book was published in 1967 by Éric Losfeld, an edition of 5000 which the publisher said he would never reprint, partly because of the expense, but also because he liked to think of the book becoming a rare object in the future. Rare it still is, although the embargo was broken in 1980, a year after Losfeld’s death, by the publication of a second edition. This was only a partial reprint, however, with a poor cover design and all the interior pages reproduced without their colour overlays.

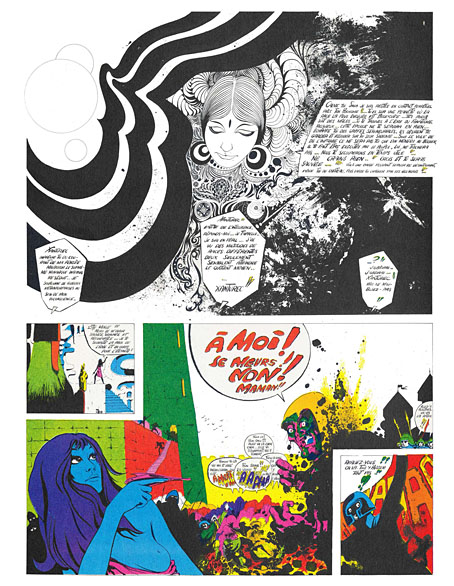

The new edition from Revival is slightly larger than the original (27.5 x 36 cm to the original 24 x 31 cm), and bound between heavy boards. A lengthy preface by Christian Staebler describes the book’s history, offering a few biographical details about Nicolas Deville (as he was known pre-1967), together with further information about the story’s creation. The wildness of the final pages is explained as an attempt by all involved to capture some of the delirium of an LSD trip, while also bringing the story of Saga’s investigation of the human race and its violent nature into the present day. Jean Rollin was apparently unhappy with this dénouement but I find the ending to be a satisfying one for a story where each chapter explores a different period of time (and of space, when Saga returns to her home planet).

The icing on the cake is the appearance near the end of a few early drawings by Philippe Druillet, together with several beautiful pages by Devil, one of which found wider circulation when reprinted as a poster. The text in the new edition is still in French, of course, and even on slightly larger pages the legibility problem from the original remains. Devil was drawing on boards that were twice the size of their printed equivalents, without caring too much whether the story would be readable when scaled to a printable size. Losfeld’s solution was to provide a magnifying glass with each copy of the book. This isn’t too much of a problem; the story is easy enough to follow once you know the general outline, and for this story it’s the art that counts more than the words.

In addition to history and biography, the preface also describes the efforts required to reprint the book. The original drawings were sold off long ago, while the pages of the original printing were deemed unsuitable for further reproduction. The artist’s son, Stan Deville, decided with Staebler to scan the black-and-white pages from the 1980 reprint then colour them to match the original. This has been very carefully done, with no discernible difference between the old and new printings. Slight differences are evident away from the comic, however, with the title pages that separate each part of the story having been reworked for reasons which aren’t explained. There’s also the anomaly of the stylised pyramid graphic that precedes the chapter set in Ancient Egypt. In the new edition this has been printed upsidedown…or possibly the right way up if the original printing was erroneous, which seems unlikely. If this is an error then it’s a forgivable one when the edition restores such a scarce volume. The book ends with a handful of extra pages showing examples of Devil’s art post-Saga, including the cover of Orejona, ou Saga Generation (1974), another collaborative work, and yet another rare book deserving a reprint. (The French apparently refer to scarce volumes such as these as “UFOs”.) Staebler’s biographical notes confirm that Devil/Deville gave up art when he moved to Canada where he became a professor of philosophy, another reason why his name and his artwork have receded over time. Online examples of his non-Saga drawings are scarce but this page has more than most.

A page featuring unmistakable Druillet figures. He also wrote the accompanying text which refers to Cthulhu and the Necronomicon.

Saga was one of a series of comic-book heroines published by Éric Losfeld in the 1960s (Barbarella, Jodelle, Pravda, et al) whose adult adventures began the evolution in bande dessinée that led eventually to Métal Hurlant and all that followed from that extraordinary magazine. Despite his influence, Losfeld often seems overlooked when the history of French comics is being discussed in Anglophone quarters. Druillet’s first Lone Sloane story, The Mystery of the Abyss, was published by Losfeld in 1966, four years before Lone Sloane was presented anew to a larger readership in Pilote magazine. Losfeld’s intentions in this area were partly exploitational—most of the stories happen to involve young women in sexual scenarios of some kind—but this was a common trend in 20th-century publishing, the publishers of erotica (or outright pornography) being more prepared than reputable publishing houses to push artistic boundaries. Saga de Xam was too lavish a project for the underground press, and too erotic and experimental for other publishers when comics in France were still being produced with a young readership in mind.

Saga de Xam remains fascinating today because it was sui generis, a much more ambitious one-off than Losfeld’s other comic books, and one that made a considerable impression before becoming the bibliographic myth that its publisher intended. Over half a century later the myth is secure enough to sustain a new edition. As Christian Staebler says at the end of his introductory text: “It is finally time to contradict Éric Losfeld and to present Saga de Xam to the eyes of the younger generations, to allow them to discover or rediscover the quintessence of the 1960s.”

I bought my copy of the book from Gallix but you’ll find it at many other French booksellers. And since my French is so poor I scanned the preface then ran it through some translation software. I’ll be keeping this on file so if anyone would like an English copy send me an email.

(My thanks once again to Goldfires for giving me the opportunity to see the pages of the original book, and to Julian for the news about the reprint!)

Previously on { feuilleton }

• The groovy look

• The Dracula Annual

• Saga de Xam revisited

• Saga de Xam by Nicolas Devil